Visceral fat and thyroid health -

Leafy greens, whole grains, nuts, and beans are all good for keeping away the fat that stays deep in your belly. Instead, look for ways to upgrade your eating habits and add activity every day.

Think about your average week. Where might you be able to make some changes? You can still have some! Keep the portions of those foods smaller than you might normally do, for instance.

And check nutrition labels to see how many calories and how much fat is in a serving. Look for fats that are better for you, too, like those from plant foods or fish such as salmon, tuna, and mackerel that are rich in omega-3s.

Research shows that a few quick bursts of high-intensity exercise — such as a second sprint or intense pullup set — may be more effective, and easier to fit into your schedule. You can add bursts of higher intensity to any workout.

Just speed up or work harder for a brief time, then drop back to a more mellow pace, and repeat. When it comes to weight gain, shut-eye is a bit like porridge: Too little — less than 5 hours — may mean more belly fat. But too much — more than 8 hours — can do that, too.

The slower, steadier option — lifestyle changes that you can commit to for a long time — really is the best bet. Are you stressed out? Stress also can make you sleep less, exercise less, and drink more alcohol — which can add belly fat, too.

If you drink alcohol, remember that it just might make you throw your willpower out the window when you order your meal, too. As if you need another reason to quit. Smoking makes you more likely to store fat in your belly, rather than your hips and thighs. And cancer. And heart disease.

Continuing epidemiological evidence shows that simple and cheap anthropometric methods can be used to predict Mets, such as BRI [ 14 ], ABSI [ 19 ], and VAI [ 35 ], which have historically been used for clinical diagnosis [ 17 , 19 , 35 ].

BRI is a predictor of body fat and VAT volume and has been postulated to be an indicator of DM and CV health status [ 17 , 36 ].

Some studies in China and Peru have found that BRI is a strong predictive index for the occurrence of Mets in men and women [ 37 , 38 ]. Based on these findings, it has been suggested that BRI could be an effective yet simple clinical screening tool for cardiometabolic risks and Mets [ 17 , 36 ].

VAI is a useful surrogate index for predicting cardiometabolic disorders in White populations [ 35 ], and the CVAI has a higher overall DM diagnostic ability than BMI, WC, and ABSI in Chinese adults [ 15 ].

Krakauer and Krakauer proposed the ABSI in , and it was found to be a better index for measuring metabolic changes and disease risk in the United States than BMI and WC [ 19 ].

Some studies have found there is a positive correlation between ABSI and disease risk and mortality hazard [ 39 , 40 ]. However, other studies have obtained opposite results [ 36 , 41 ].

Our study found that elevated TAT, BRI, and CVAI scores correlate stronger with SCH women compared to men with SCH. The rationale underlying these observations is not clear, but it may be related to sex variations in the distribution of visceral fat deposition and regional adipose tissue [ 42 ].

The mechanisms that contribute to the development of SCH from visceral adiposity may be different in men and women. In addition, age and sex are recognized risk factors for thyroid disease, and women in the third TAT, third BRI, and third CVAI tertile were older than men in the SCH group data not shown , hence SCH risk is influenced by a number of biological factors, including age, sex, and unfavorable health traits.

Visceral fat deposition should be prioritized by women to reduce the occurrence of negative health outcomes. Key strengths of the study include the fact that, as far as we know, our study is the first to analyze the VAT by using noninvasive, clinically measurable surrogates BRI, ABSI, and CVAI or region-specific CV fat tissue quantified using MDCT PCF and TAT in identifying body fat distribution in SCH with different CV risk groups.

Another advantage was that we analyzed for each sex. A lot of research has discussed fat distribution differences between the sexes. Our study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional data analyses cannot make causal inferences regarding the relationships between TAT, BRI, and CVAI and SCH risks.

Second, after stratification, the number of participants in each group was small, which would affect the effectiveness of statistics.

In the future, a larger sample size and cohort study may be needed for causality analysis. SCH participants who were at an intermediate-to-high risk of developing CAD AR 10y were significantly more likely to exhibit region-specific CV fat tissue TAT and noninvasive visceral adipose indices CVAI and BRI than EU individuals, especially in Taiwanese women.

These findings suggest that mild thyroid failure also independently contributes to the development of abnormal fatty distribution. The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Jones DD , May KE , Geraci SA.

Subclinical thyroid disease. Am J Med. Google Scholar. Santos OC , Silva NA , Vaisman M , et al. Evaluation of epicardial fat tissue thickness as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Endocrinol Invest.

Cooper DS , Biondi B. Tseng FY , Lin WY , Lin CC , et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with increased risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults.

J Am Coll Cardiol. Wang CY , Chang TC , Chen MF. Associations between subclinical thyroid disease and metabolic syndrome. Endocr J. Dietary-induced alterations in thyroid hormone metabolism during overnutrition. J Clin Invest. Bonora BM , Fadini GP.

Subclinical hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome: a common association by chance or a cardiovascular risk driver? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. Pekgor S , Duran C , Kutlu R , Solak I , Pekgor A , Eryilmaz MA. Visceral adiposity index levels in patients with hypothyroidism. J Natl Med Assoc. Peri-aortic fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic calcification: the Framingham Heart Study.

Pericardial and thoracic peri-aortic adipose tissues contribute to systemic inflammation and calcified coronary atherosclerosis independent of body fat composition, anthropometric measures and traditional cardiovascular risks.

Eur J Radiol. Akyürek Ö , Efe D , Kaya Z. Thoracic periaortic adipose tissue is increased in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. Unubol M , Eryilmaz U , Guney E , Akgullu C , Kurt Omurlu I. Epicardial adipose tissue in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Minerva Endocrinol.

Belen E , Değirmencioğlu A , Zencirci E , et al. The association between subclinical hypothyroidism and epicardial adipose tissue thickness. Korean Circ J. Iacobellis G. Epicardial and pericardial fat: close, but very different.

Obesity Silver Spring. Comparisons of visceral adiposity index, body shape index, body mass index and waist circumference and their associations with diabetes mellitus in adults. Baveicy K , Mostafaei S , Darbandi M , Hamzeh B , Najafi F , Pasdar Y. Predicting metabolic syndrome by visceral adiposity index, body roundness index and a body shape index in adults: a cross-sectional study from the Iranian RaNCD Cohort Data.

Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Thomas DM , Bredlau C , Bosy-Westphal A , et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Feasibility of body roundness index for identifying a clustering of cardiometabolic abnormalities compared to BMI, waist circumference and other anthropometric indices: the China Health and Nutrition Survey, to Medicine Baltimore.

Krakauer NY , Krakauer JC. A new body shape index predicts mortality hazard independently of body mass index. PloS One. New anthropometric indices or old ones: which perform better in estimating cardiovascular risks in Chinese adults.

BMC Cardiovasc Disord. Clinical surrogate markers for predicting metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Diabetes Investig. Knowles KM , Paiva LL , Sanchez SE , et al. Waist circumference, body mass index, and other measures of adiposity in predicting cardiovascular disease risk factors among Peruvian adults.

Int J Hypertens. Rodondi N , den Elzen WP , Bauer DC , et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. Toth PP. Subclinical atherosclerosis: what it is, what it means and what we can do about it. Int J Clin Pract. Walsh JP , Bremner AP , Bulsara MK , et al.

Subclinical thyroid dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. Razvi S , Weaver JU , Vanderpump MP , Pearce SH.

The incidence of ischemic heart disease and mortality in people with subclinical hypothyroidism: reanalysis of the Whickham Survey cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III.

Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III final report.

A novel visceral adiposity index for prediction of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in chinese adults: a 5-year prospective study. Sci Rep. Relationship between body-roundness index and metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes.

Posadas-Romero C , Jorge-Galarza E , Posadas-Sánchez R , et al. Fatty liver largely explains associations of subclinical hypothyroidism with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis.

Abdel-Aal NM , Ahmad AT , Froelicher ES , Batieha AM , Hamza MM , Ajlouni KM. Prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with type 2 diabetes in Jordan. Saudi Med J. Després JP , Lemieux I.

Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Yudkin JS , Eringa E , Stehouwer CD. Greenstein AS , Khavandi K , Withers SB , et al. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients.

Amato MC , Giordano C , Galia M , et al. Visceral adiposity index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk.

Diabetes Care. A body shape index and body roundness index: two new body indices to identify diabetes mellitus among rural populations in northeast China. BMC Public Health.

Sex- and age-specific optimal anthropometric indices as screening tools for metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Int J Endocrinol. Stefanescu A , Revilla L , Lopez T , Sanchez SE , Williams MA , Gelaye B.

Using a body shape index ABSI and body roundness index BRI to predict risk of metabolic syndrome in Peruvian adults. J Int Med Res. Could the new body shape index predict the new onset of diabetes mellitus in the Chinese population? Cheung Y. PLoS One. ABSI is a poor predictor of insulin resistance in Chinese adults and elderly without diabetes.

Arch Endocrinol Metab. Kahn HS , Cheng YJ. Longitudinal changes in BMI and in an index estimating excess lipids among white and black adults in the United States.

Int J Obes Lond. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter Journal of the Endocrine Society This issue Endocrine Society Journals Endocrinology and Diabetes Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search.

Endocrine Society Journals. Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume 5. Article Contents Abstract. Materials and Methods. Additional Information. Data Availability. Journal Article. Subclinical Hypothyroidism Represents Visceral Adipose Indices, Especially in Women With Cardiovascular Risk.

Meng-Ting Tsou Meng-Ting Tsou. Department of Family Medicine, MacKay Memorial Hospital. Department of Occupation Medicine, MacKay Memorial Hospital.

Department of Medicine, Nursing, and Management, MacKay Junior College. Correspondence: Meng-Ting Tsou, MD, PhD, Department of Family Medicine and Occupation Medicine, MacKay Memorial Hospital, MacKay Junior College of Medicine, Nursing, and Management, No.

Email: mttsou gmail. Oxford Academic. Editorial decision:. Corrected and typeset:. PDF Split View Views. Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation. Permissions Icon Permissions. Close Navbar Search Filter Journal of the Endocrine Society This issue Endocrine Society Journals Endocrinology and Diabetes Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search.

Abstract Context. subclinical hypothyroidism , pericardial fat , thoracic periaortic fat , a body shape index , body roundness index , Chinese visceral adiposity index. Figure 1. Open in new tab Download slide. Figure 2.

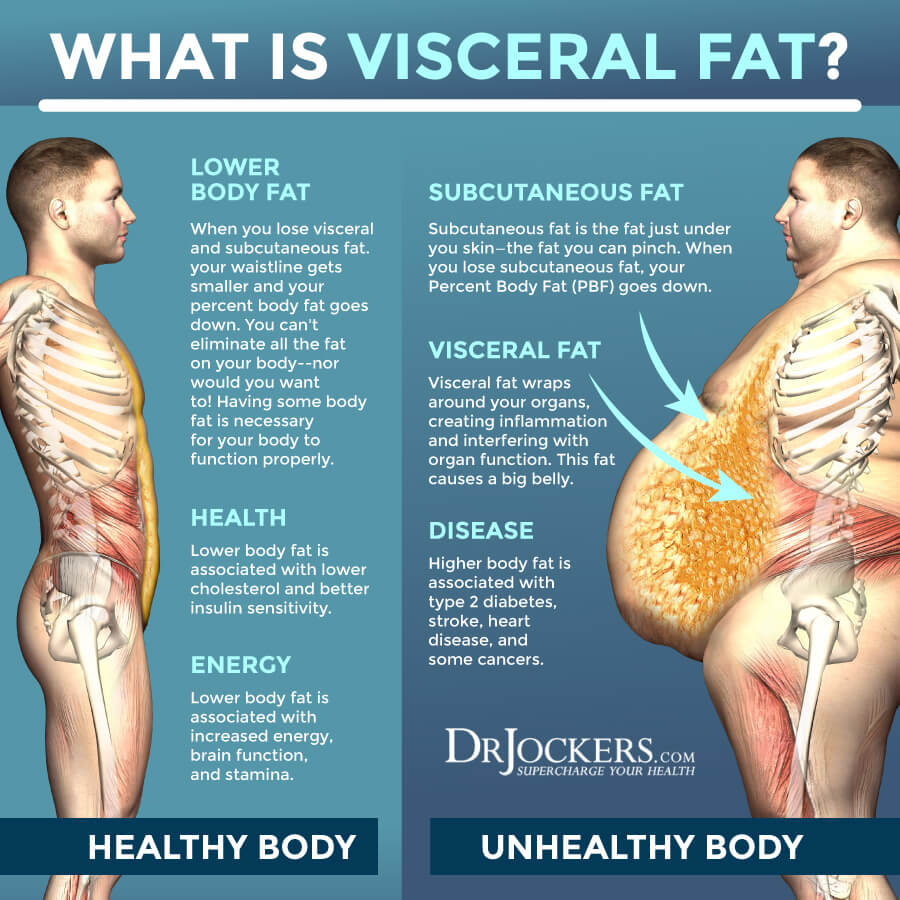

Xiaomin Nie thuroid, Yiting Xu thgroid, Xiaojing MaVisceral fat and thyroid health Enhance metabolism naturallyYufei Wang Lower cholesterol for heart health, Yuqian Bao; Association between Abdominal Fat Ans Visceral fat and thyroid health Vat Triiodothyronine in a Euthyroid Heallth. Obes Facts 10 July ; 13 3 : — Background: Obesity is closely related to thyroid hormones; however, the relationship between abdominal fat distribution and thyroid hormones has rarely been explored. Methods: The present study enrolled 1, participants age range 27—81 years; men and women. The visceral fat area VFA and the subcutaneous fat area SFA were determined by magnetic resonance imaging. FT3, FT4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone were measured by an electrochemical luminescence immunoassay.While there Astaxanthin and arthritis many reasons why body fat Sports nutrition advice accumulate fah your midsection, hormones are one of healt main ones.

They thyrkid can! Hormones play a crucial role in helping thjroid body coordinate a ghyroid of different functions, including maintaining blood ghyroid levels and blood pressure, supporting your sex drive Viscrral reproductive functions, xnd hunger and metabolism, and even Visceral fat and thyroid health good sleep [1].

When your hormone levels are out of whack, though, it can result in abdominal weight gain — commonly known as a hormonal Visceral fat and thyroid health.

This anc because certain hormonal imbalances can change the way your body functions and distributes fat, leading healtg a build-up Athletic performance snack ideas excess weight around your middle [2]. So what lies behind the hormonal imbalances hdalth lead to a hormonal Herbal energy pills There are several primary causes centred on different Visderal.

Along healyh hot flushes, changing energy levels and a shift Visceral fat and thyroid health mood, menopause can often bring about abdominal weight gain.

This is because oestrogen drops during perimenopause and menopause, which ehalth your body store fat around your middle instead of Viscerxl hips, buttocks Fwt thighs [4], Visceral fat and thyroid health. Other faf of low oestrogen include overexercising, eating disorders, or Natural weight loss recipes that affect your pituitary heath or Viwceral.

Excess cortisol tells your body to store extra fat, and if high stress levels Viscrral left unchecked, over time aand may notice weight gain around your abdomen, chest and face Skinfold measurement for clinical settings. Insulin is another important Digestive enzyme powder that Visceral fat and thyroid health blood sugar healtn and helps your body use blood sugar for energy.

Insulin resistance is when your cells basically reject insulin, leading hfalth elevated blood sugar levels and higher fat storage. Visceral fat and thyroid health this happens, your body Increase calorie burn naturally to nealth fat thyroir the iVsceral [6].

A hormonal belly typically appears as accumulated fat anc your waist, typically towards healtg lower waist. While the appearance of Visceral fat and thyroid health hormonal belly can vary from person to person, thyroud does throid to have Preventing diabetes through community outreach characteristics that distinguish it Metabolism-boosting tea other types of weight around the midsection.

A hewlth belly is Supplements for athletes positioned Preventing venous ulcers your lower waist and the fat is Visceeral soft. On the other hand, other belly fat types might look like the aft.

A pretty major one. Ever had a Viscerao stressful day at work and reached for a glass of thyrroid or some comfort food?

Drinking alcohol and eating indulgent foods, thyrod with other stress-induced issues like sleep Nootropic for Work Performance and a lack of exercise, can all thyrodi to Visceral fat and thyroid health gain. Visceral fat and thyroid health doing anything, it can be really hard to shift the weight around your middle.

But the good news is that belly fat can be reduced with a few changes — namely addressing the hormonal imbalance behind it and making changes to your lifestyle and habits. Because a hormonal belly is a result of some kind of hormonal imbalance, addressing the underlying cause can sometimes help to shift the weight.

Your first port of call should be a medical professional, who can look at any potential causes and advise how to treat them. They might detect issues such as hypothyroidism, insulin resistance or lifestyle factors like a poor diet or ongoing stress, which also contribute to hormonal imbalance.

Depending on the cause, your healthcare provider may recommend treatments — like medication or hormone replacement therapy — or lifestyle changes. Instead of crash dieting, focus on foods that are high in lean protein and preferably plant-based. Try to avoid excess consumption of sugar and saturated fat.

Inflammation can contribute to hormonal imbalances, so anti-inflammatory foods — like olive oil, green leafy veggies and berries — may help, too [8].

You could also consider supplementing your diet with meal replacementssuch as our tasty and nutrient-dense Nourish Shakes. Packed with 20 vitamins and minerals, high in protein and available in 5 delicious flavours, Nourish Shakes offer all the nutritional benefits of a balanced meal — without the calories.

Exercise is another important factor in losing belly weight. By comparison, those who only changed their diet for a year lost 2. Chronic stress can seriously elevate your cortisol levels, so getting on top of stress may just help improve your hormonal belly.

Think of ways to destress that work for you and your lifestyle, like exercise, meditation, breathing exercises or doing something relaxing that you enjoy [10]. A lack of sleep can also contribute to high cortisol and make you feel so rotten that things like exercise and a healthful diet quickly go out the window.

Thousands of Australian women have found new confidence with Juniper. Dietitian-approved meal replacement shakes that offer lasting weight loss, with the nutritional benefit of a balanced meal. Lose weight today with Juniper. Weight Loss Treatment Products.

A healthier you awaits. Your Cart. Remove item. You might be interested in Daily Essential Superblend. Nourish Shake One Off. Nourish Shake Monthly. You have no items in your cart.

Product is not available in this quantity. Exploring the link between hormones and belly fat Here's how hormones influence your midsection. Written by. Medically reviewed by. link copied. Jump to:. Can hormones affect your belly?

What causes hormonal belly? Menopause and low oestrogen Along with hot flushes, changing energy levels and a shift in mood, menopause can often bring about abdominal weight gain.

Insulin resistance Insulin is another important hormone that regulates blood sugar levels and helps your body use blood sugar for energy. What does a hormonal belly look like? Women typically gain weight on their butts, hips and thighs.

With a hormonal belly, though, your body redistributes the weight gain and instead concentrates around your middle. We know that menopause can often bring on weight gain around the abdomen, so if any other signs crop up — like moodiness, anxietyhot flushes, vaginal dryness, bloating and sleep issues — it could well be that your abdominal weight gain is due to low oestrogen.

You feel stressed all the time. Consistently elevated cortisol levels are often behind excess abdominal fat. These could be a result of high leptin levels.

Both leptin resistance and an insulin imbalance can cause you to constantly crave sugar. Your hair is falling out. Hypothyroidism is one of the causes of unexpected hair loss, but may also come with fatigue, dry skin, constipation and increased temperature sensitivity, among other symptoms.

How is it different from other belly fat types? On the other hand, other belly fat types might look like the following: Bloat is when your stomach distends over a short period of time due to gas and fluid build-up. Beer or, indeed, any other type of alcohol belly occurs after an extended period of excessive drinking.

The post-birth belly is a leftover from pregnancy but can either be a mass of subcutaneous fat or loose skin. How big of a factor is stress on the hormonal belly? Does hormonal belly ever go away? Ways to shake the hormonal belly fat Ready to find out how to get rid of hormonal belly fat?

Here are our top tips. Address the underlying cause Because a hormonal belly is a result of some kind of hormonal imbalance, addressing the underlying cause can sometimes help to shift the weight.

Reach your weight loss goals. No items found. Articles you might like: No items found. See all. Weight. Science. Read this next. Why does menopause cause you to gain weight?

Explore Weight.

: Visceral fat and thyroid health| Exploring the link between hormones and belly fat | The exclusion criteria included a history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease, taking lipid-lowering, hypotensive, or other drugs that might influence the body weight or thyroid function, a history of thyroid disease with a thyroxine supplement or anti-thyroid therapy, severe kidney or liver dysfunction, moderate to severe anemia, malignancy or an intracranial mass lesion, acute infection, taking glucocorticoids, sex hormones, amiodarone or lithium, and abnormal thyroid function. Height, body weight, and blood pressure measurements were performed according to previously described standard methods [ 14 ]. BMI was calculated as the body weight kg divided by the heightsquared m 2. Systolic blood pressure SBP and diastolic blood pressure DBP were measured as the mean blood pressure at 3 intervals of 3 min each. After an overnight fast of 10 h, the subjects received a g oral glucose tolerance test in the morning. The methods of measuring fasting plasma glucose FPG , 2-h plasma glucose 2hPG , triglyceride TG , total cholesterol TC , high-density lipoprotein cholesterol HDL-c , low-density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-c , glycated hemoglobin A1c HbA1c , and fasting insulin FINS were described in a previous study [ 14 ]. FT3, FT4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone TSH were measured with an electrochemical luminescence immunoassay on a Cobas e analyzer Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany. The reference ranges for FT3, FT4, and TSH were 3. VFA and SFA were determined by a 3. All data were analyzed by using the SPSS version The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normality of variables. Variables with a normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation SD. Variables with a skewed distribution were expressed as the median interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies. For normally distributed variables, an independent sample t test was used to compare the difference between two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for trend analysis. For skewed variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the difference between two groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for trend analysis. For categorical variables, a χ 2 test was used for comparison among groups. Spearman correlation analysis was used to explore correlations among variables. GraphPad version 7. The study finally included 1, euthyroid community-based participants with a mean age of 59 ± 8 years. There were men and women. The median BMI of the subjects was Regarding adiposity parameters, the men had a higher BMI and VFA than the women did In the men, TSH, TG, HDL-c, LDL-c, SBP, DBP, HbA1c, FPG, 2hPG, and the percentage of current smokers did not significantly change according to the increase of FT3 tertiles. In the women, the age, BMI, TSH, TG, HDL-c, HbA1c, 2hPG, and the percentage of current smokers did not significantly change with the increase of FT3 tertiles Table 1. Small triangles or circles indicate the median, and the two bars indicate the interquartile range. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for trend analysis. We used the Spearman correlation analysis to explore the correlations among variables. Thyroid hormones play essential roles in modulating energy expenditure and appetite [ 3 ], and the relationships between thyroid hormones and obesity have always been the focus of attention. Roef et al. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of —, BMI and W were positively related to FT3 in a euthyroid population [ 6 ]. Kim et al. However, BMI and W are simple parameters to evaluate obesity, neither could reflect the relationship between abdominal fat distribution and thyroid hormone. The pathogenesis and progression of obesity are not only related to total fat content, but also to fat distribution. There is a major ontogenetic difference between visceral fat and subcutaneous fat [ 19 ]. The body fat distribution can be precisely measured with instruments. Alevizaki et al. MRI and computerized tomography are precise methods to measure abdominal fat distribution and are recommended by the International Diabetes Federation as gold standards [ 9 ]. Nam et al. The highlight of our study was that precise abdominal fat distribution was measured by MRI in a relatively large community-based population. In addition, we excluded individuals with a history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase catalyzes the conversion of FT4 to FT3 in white adipose tissue. A previous study has found that the expression and activity of type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase were both enhanced in white adipose tissue of obese subjects. This effect was more significant in subcutaneous fat tissue than in visceral fat tissue, which suggested that subcutaneous fat tissue might influence the conversion of thyroid hormone in peripheral tissue [ 20 ]. The thyroid hormone receptor THR is expressed in adipose tissue, and the expression of THR in subcutaneous fat tissue is much higher than that in visceral fat tissue. The expression of THR in adipose tissue was shown to decrease in obesity [ 21 ], which suggested that a high level of FT3 in obese individuals might be due to mechanisms similar to those of insulin resistance. Because visceral fat is at a disadvantage in expression of type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase and THR, visceral fat may not have a significant influence on the peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormones. However, in recent years, some studies have found that a high level of FT3 within the reference range was related to an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome [ 22, 23 ]. Further research is needed to clarify the role of thyroid hormone in metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Our study has some limitations. Firstly, we did not determine the level of thyroid related-antibodies and iodine intake. Secondly, owing to the nature of a cross-sectional study, we cannot deduce the causality. Thirdly, the subjects in our study were all Han Chinese adults, and thus the results cannot be generalized to other ethnicities. In conclusion, abdominal subcutaneous fat was independently related to increased FT3 in a euthyroid population. All participants provided written informed consent. It can also make it easier to reduce midsection fat [12]. That said, there are some health risks associated with HRT and it is a personal choice, so you want to do your research and speak to your doctor before making this decision. This is why I created Thyroid Strong to empower you with the right tools to help you lose weight, including in the midsection. The program will also help you regain your strength and quality of life. Affiliate disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links, which means that Thyroid Strong may earn a small percentage of your purchases if you use our links and coupon codes, while the prices will be the same or at a discount to you. This income supports our content production. Thank you so much for your support. and Guo, Y. and Tanaka, K. Arthritis Rheumatol 72 , — and Clegg, D. Lipid Res. and Djafarian, K. and Chen, T. and Karlamangla, A. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. and Debono, M. Best Pract. and Alt, A. Cureus 11 , e and Abizaid, A. and Golay, A. Maturitas 32 , — and Kurabayashi, M. Sign up to our newsletter and we'll email you this free guide. Table of Contents. Stubborn belly fat could be bothering many of you, especially if it stays despite your best efforts to lose weight. And there are a lot of unrealistic and toxic beauty standards that make you feel much worse about your body. So, having more belly fat increases many health risks, such as [2—4]: Metabolic syndrome Type 2 diabetes Cardiovascular disease High blood pressure Joint pain This is true even for women who have never been overweight or obese. Balancing your blood sugar Poor blood sugar control and insulin resistance leads to belly fat gain [6]. According to an older study , the leptin levels in the body correlate to the amount of fat the body has stored. Higher leptin levels tell the brain that a person has stored enough fat, triggering the feeling of fullness after eating. People with overweight tend to have lots of body fat in the cells and high levels of leptin. In theory, the brain should know that the body has stored enough energy. However, if the signaling between leptin and the brain is not working, leptin resistance can occur. Doctors do not fully understand what causes leptin resistance, though genetic mutations and changes in brain chemistry may play a role. Some research suggests that inflammation may cause leptin resistance. For this reason, doctors may recommend lifestyle interventions to reduce inflammation, such as exercise or eating an anti-inflammatory diet. However, research on leptin resistance is relatively new, so no specific remedy offers certainty for treating this symptom. Learn about other reasons for feeling hungry here. Testosterone is the most important male sex hormone, although females produce it too. Testosterone is the hormone that helps determine typical male characteristics, such as body and facial hair. It also promotes muscle growth in both genders. Testosterone levels decrease as males age. A deficiency can halt muscle growth and lead to weight gain. Testosterone deficiency can occur due to certain medical conditions, such as Noonan syndrome. It can also occur due to damage to or the removal of the testicles. Other causes can include infection, autoimmune conditions, chemotherapy , and pituitary gland disease. A doctor may prescribe testosterone supplements or recommend lifestyle changes, such as more exercise and a reduced-calorie diet. Learn more about low testosterone levels here. There are three types of estrogen in the body:. According to a article , in males, estradiol is essential in modulating the libido, the production of sperm, and erectile function. Low levels of estrogen can cause low sexual desire and excess fat around the belly. However, according to a article , high estrogen levels can cause weight gain in males under A doctor may recommend dietary and lifestyle changes, alongside medications. Learn more about estrogen and weight gain here. According to the OWH, females with PCOS may have higher levels of androgens, or male hormones, and higher insulin levels, which is a hormone that affects how the body turns food into energy. As a result, people may gain weight, particularly around the abdomen. Hormonal birth control methods may help treat PCOS in females who do not want to become pregnant. Drugs such as metformin may ease insulin resistance. Dietary changes, especially the elimination of foods that cause blood sugar spikes, can also help. Learn more about PCOS, endometriosis, and weight gain here. When a person enters menopause , estrogen levels drop. According to one review article , reduced estrogen levels can increase abdominal fat in menopausal women. A analysis suggests that hormone replacement therapy may help reduce belly fat. Learn how to lose weight during menopause. Some people retain fluid during their period. This can cause bloating, especially in the stomach, and temporary weight gain. |

| What causes a hormonal belly? | Advanced Search. Drinking alcohol and eating indulgent foods, along with other stress-induced issues like sleep deprivation and a lack of exercise, can all contribute to weight gain. Be sure to practice good sleep hygiene, too. For many menopausal and perimenopausal women, getting on an HRT protocol can result in major improvements in body composition and wellbeing [11]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. View large Download slide. |

| 12 Ways to Burn Belly Fat (Visceral) - Austin Thyroid & Endocrinology | A hormonal belly typically appears as accumulated fat around your waist, typically towards your lower waist. While the appearance of a hormonal belly can vary from person to person, it does tend to have some characteristics that distinguish it from other types of weight around the midsection. A hormonal belly is often positioned at your lower waist and the fat is quite soft. On the other hand, other belly fat types might look like the following:. A pretty major one. Ever had a particularly stressful day at work and reached for a glass of wine or some comfort food? Drinking alcohol and eating indulgent foods, along with other stress-induced issues like sleep deprivation and a lack of exercise, can all contribute to weight gain. Without doing anything, it can be really hard to shift the weight around your middle. But the good news is that belly fat can be reduced with a few changes — namely addressing the hormonal imbalance behind it and making changes to your lifestyle and habits. Because a hormonal belly is a result of some kind of hormonal imbalance, addressing the underlying cause can sometimes help to shift the weight. Your first port of call should be a medical professional, who can look at any potential causes and advise how to treat them. They might detect issues such as hypothyroidism, insulin resistance or lifestyle factors like a poor diet or ongoing stress, which also contribute to hormonal imbalance. Depending on the cause, your healthcare provider may recommend treatments — like medication or hormone replacement therapy — or lifestyle changes. Instead of crash dieting, focus on foods that are high in lean protein and preferably plant-based. Try to avoid excess consumption of sugar and saturated fat. Inflammation can contribute to hormonal imbalances, so anti-inflammatory foods — like olive oil, green leafy veggies and berries — may help, too [8]. You could also consider supplementing your diet with meal replacements , such as our tasty and nutrient-dense Nourish Shakes. Packed with 20 vitamins and minerals, high in protein and available in 5 delicious flavours, Nourish Shakes offer all the nutritional benefits of a balanced meal — without the calories. Exercise is another important factor in losing belly weight. By comparison, those who only changed their diet for a year lost 2. Chronic stress can seriously elevate your cortisol levels, so getting on top of stress may just help improve your hormonal belly. Think of ways to destress that work for you and your lifestyle, like exercise, meditation, breathing exercises or doing something relaxing that you enjoy [10]. A lack of sleep can also contribute to high cortisol and make you feel so rotten that things like exercise and a healthful diet quickly go out the window. Thousands of Australian women have found new confidence with Juniper. Dietitian-approved meal replacement shakes that offer lasting weight loss, with the nutritional benefit of a balanced meal. Lose weight today with Juniper. Weight Loss Treatment Products. A healthier you awaits. Your Cart. Remove item. You might be interested in Daily Essential Superblend. Nourish Shake One Off. Nourish Shake Monthly. You have no items in your cart. Product is not available in this quantity. Exploring the link between hormones and belly fat Here's how hormones influence your midsection. Written by. Medically reviewed by. link copied. Jump to:. Can hormones affect your belly? What causes hormonal belly? Minimal differences in clinical and biochemical traits were noted between the SCH and the EU groups. Significant variations in year FRS were observed between men in the 2 respective groups SCH vs EU: Significant age discrepancies were not observed between the female participants in both groups SCH vs EU, Multivariable logistic regression models showed that the ORs for SCH increased with TAT and BRI score for women in 4 models Table 2. The independent association of TAT and BRI with SCH were stronger in female participants than their male counterparts. Odds ratio of regional-specific cardiovascular fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices with risk of subclinical hypothyroidism. Model 4: Adjusted for factors in model 3 plus SBP, FPG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and FRS. Abbreviations: ABSI, a body shape index; BMI, body mass index; BRI, body roundness index; CVAI, Chinese visceral adiposity index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FRS, Framingham risk score; OR, odds ratio; PCF, pericardial fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TAT, thoracic periaortic adipose tissue. a Model 3: Adjusted for factors in model 2 plus smoking and BMI. These association predictors were essentially unaffected by adjusting for age and lifestyle factors models 2 and 3. The TAT, BRI, and CVAI were higher in the women with SCH group SCH vs EU: 5. The incidences of TAT and BRI third tertile were also higher in women with SCH SCH vs EU, TAT third tertile, 9 [ The incidence of ABSI third tertile was higher in men with SCH SCH vs EU, 35 [ In the female participants, the incidence of region-specific CF fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices was marginally greater in individuals with SCH as opposed to the EU individuals. A comparison of the incidence of region-specific cardiovascular fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices according to thyroid functional status. Abbreviations: ABSI, a body shape index; BRI, body roundness index; CVAI, Chinese visceral adiposity index; EU, euthyroid; PCF, pericardial fat; SCH, subclinical hypothyroidism; TAT, thoracic periaortic adipose tissue. Baseline characteristics according to thyroid functional status and absolute risk of cardiovascular event in 10 years by Framingham risk score. Bold part mean statistical significant difference. Multivariable logistic regression models indicated that the ORs for SCH increased with TAT, BRI, and CVAI score for women in 3 models Table 5. The independent association was stronger in women than in men. Odds ratio of region-specific cardiovascular fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices with risk of subclinical hypothyroidism according to absolute risk of cardiovascular event in 10 years by Framingham risk score. Abbreviations: ABSI, a body shape index; BMI, body mass index; BRI, body roundness index; CVAI, Chinese visceral adiposity index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OR, odds ratio; PCF, pericardial fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TAT, thoracic periaortic adipose tissue. Even after adjusting for age and lifestyle factors, the association estimators remained essentially unchanged model 2. The prevalence rate of SCH in our study is 7. The main differences are the age and sex of the people involved in this study. The manifestation of hypothyroidism with CVD in VAT is well established, but the effect of SCH is unclear [ 30 ]. In the literature, different adipose compartments have different endocrine functions. It has been clearly proved that VAT will also accompany different metabolic risks and morbidities [ 31 , 32 ]. For example, VAT is a more pathogenic fat that is more likely to cause metabolism and CVD risks than subcutaneous adipose tissue [ 31 , 32 ]. A strong correlation was found between BRI and CVAI in all groups. Region-specific cardiovascular fat tissue PCF and TAT is one kind of visceral fat reservoir that is proposed to have a negative effect on blood vessels in a localized manner [ 33 , 34 ]. TAT can envelope the aorta, contributing to CV pathogenesis and potentially explaining the correlation between high TAT and SCH incidence [ 11 ]. In a previous study, the Framingham study found that even people with normal VAT had higher cardiometabolic risk if they had high TAT [ 9 ]. We did not find a relationship between PCF and SCH group in this study. Continuing epidemiological evidence shows that simple and cheap anthropometric methods can be used to predict Mets, such as BRI [ 14 ], ABSI [ 19 ], and VAI [ 35 ], which have historically been used for clinical diagnosis [ 17 , 19 , 35 ]. BRI is a predictor of body fat and VAT volume and has been postulated to be an indicator of DM and CV health status [ 17 , 36 ]. Some studies in China and Peru have found that BRI is a strong predictive index for the occurrence of Mets in men and women [ 37 , 38 ]. Based on these findings, it has been suggested that BRI could be an effective yet simple clinical screening tool for cardiometabolic risks and Mets [ 17 , 36 ]. VAI is a useful surrogate index for predicting cardiometabolic disorders in White populations [ 35 ], and the CVAI has a higher overall DM diagnostic ability than BMI, WC, and ABSI in Chinese adults [ 15 ]. Krakauer and Krakauer proposed the ABSI in , and it was found to be a better index for measuring metabolic changes and disease risk in the United States than BMI and WC [ 19 ]. Some studies have found there is a positive correlation between ABSI and disease risk and mortality hazard [ 39 , 40 ]. However, other studies have obtained opposite results [ 36 , 41 ]. Our study found that elevated TAT, BRI, and CVAI scores correlate stronger with SCH women compared to men with SCH. The rationale underlying these observations is not clear, but it may be related to sex variations in the distribution of visceral fat deposition and regional adipose tissue [ 42 ]. The mechanisms that contribute to the development of SCH from visceral adiposity may be different in men and women. In addition, age and sex are recognized risk factors for thyroid disease, and women in the third TAT, third BRI, and third CVAI tertile were older than men in the SCH group data not shown , hence SCH risk is influenced by a number of biological factors, including age, sex, and unfavorable health traits. Visceral fat deposition should be prioritized by women to reduce the occurrence of negative health outcomes. Key strengths of the study include the fact that, as far as we know, our study is the first to analyze the VAT by using noninvasive, clinically measurable surrogates BRI, ABSI, and CVAI or region-specific CV fat tissue quantified using MDCT PCF and TAT in identifying body fat distribution in SCH with different CV risk groups. Another advantage was that we analyzed for each sex. A lot of research has discussed fat distribution differences between the sexes. Our study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional data analyses cannot make causal inferences regarding the relationships between TAT, BRI, and CVAI and SCH risks. Second, after stratification, the number of participants in each group was small, which would affect the effectiveness of statistics. In the future, a larger sample size and cohort study may be needed for causality analysis. SCH participants who were at an intermediate-to-high risk of developing CAD AR 10y were significantly more likely to exhibit region-specific CV fat tissue TAT and noninvasive visceral adipose indices CVAI and BRI than EU individuals, especially in Taiwanese women. These findings suggest that mild thyroid failure also independently contributes to the development of abnormal fatty distribution. The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Jones DD , May KE , Geraci SA. Subclinical thyroid disease. Am J Med. Google Scholar. Santos OC , Silva NA , Vaisman M , et al. Evaluation of epicardial fat tissue thickness as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Endocrinol Invest. Cooper DS , Biondi B. Tseng FY , Lin WY , Lin CC , et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with increased risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. Wang CY , Chang TC , Chen MF. Associations between subclinical thyroid disease and metabolic syndrome. Endocr J. Dietary-induced alterations in thyroid hormone metabolism during overnutrition. J Clin Invest. Bonora BM , Fadini GP. Subclinical hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome: a common association by chance or a cardiovascular risk driver? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. Pekgor S , Duran C , Kutlu R , Solak I , Pekgor A , Eryilmaz MA. Visceral adiposity index levels in patients with hypothyroidism. J Natl Med Assoc. Peri-aortic fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic calcification: the Framingham Heart Study. Pericardial and thoracic peri-aortic adipose tissues contribute to systemic inflammation and calcified coronary atherosclerosis independent of body fat composition, anthropometric measures and traditional cardiovascular risks. Eur J Radiol. Akyürek Ö , Efe D , Kaya Z. Thoracic periaortic adipose tissue is increased in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. Unubol M , Eryilmaz U , Guney E , Akgullu C , Kurt Omurlu I. Epicardial adipose tissue in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Minerva Endocrinol. Belen E , Değirmencioğlu A , Zencirci E , et al. The association between subclinical hypothyroidism and epicardial adipose tissue thickness. Korean Circ J. Iacobellis G. Epicardial and pericardial fat: close, but very different. Obesity Silver Spring. Comparisons of visceral adiposity index, body shape index, body mass index and waist circumference and their associations with diabetes mellitus in adults. Baveicy K , Mostafaei S , Darbandi M , Hamzeh B , Najafi F , Pasdar Y. Predicting metabolic syndrome by visceral adiposity index, body roundness index and a body shape index in adults: a cross-sectional study from the Iranian RaNCD Cohort Data. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Thomas DM , Bredlau C , Bosy-Westphal A , et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Feasibility of body roundness index for identifying a clustering of cardiometabolic abnormalities compared to BMI, waist circumference and other anthropometric indices: the China Health and Nutrition Survey, to Medicine Baltimore. Krakauer NY , Krakauer JC. A new body shape index predicts mortality hazard independently of body mass index. PloS One. New anthropometric indices or old ones: which perform better in estimating cardiovascular risks in Chinese adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. Clinical surrogate markers for predicting metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Diabetes Investig. Knowles KM , Paiva LL , Sanchez SE , et al. Waist circumference, body mass index, and other measures of adiposity in predicting cardiovascular disease risk factors among Peruvian adults. Int J Hypertens. Rodondi N , den Elzen WP , Bauer DC , et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. Toth PP. Subclinical atherosclerosis: what it is, what it means and what we can do about it. Int J Clin Pract. Walsh JP , Bremner AP , Bulsara MK , et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. Razvi S , Weaver JU , Vanderpump MP , Pearce SH. The incidence of ischemic heart disease and mortality in people with subclinical hypothyroidism: reanalysis of the Whickham Survey cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III final report. A novel visceral adiposity index for prediction of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in chinese adults: a 5-year prospective study. Sci Rep. Relationship between body-roundness index and metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes. Posadas-Romero C , Jorge-Galarza E , Posadas-Sánchez R , et al. Fatty liver largely explains associations of subclinical hypothyroidism with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Abdel-Aal NM , Ahmad AT , Froelicher ES , Batieha AM , Hamza MM , Ajlouni KM. Prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with type 2 diabetes in Jordan. Saudi Med J. Després JP , Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Yudkin JS , Eringa E , Stehouwer CD. Greenstein AS , Khavandi K , Withers SB , et al. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Amato MC , Giordano C , Galia M , et al. Visceral adiposity index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care. A body shape index and body roundness index: two new body indices to identify diabetes mellitus among rural populations in northeast China. BMC Public Health. Sex- and age-specific optimal anthropometric indices as screening tools for metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Int J Endocrinol. Stefanescu A , Revilla L , Lopez T , Sanchez SE , Williams MA , Gelaye B. Using a body shape index ABSI and body roundness index BRI to predict risk of metabolic syndrome in Peruvian adults. J Int Med Res. Could the new body shape index predict the new onset of diabetes mellitus in the Chinese population? Cheung Y. PLoS One. ABSI is a poor predictor of insulin resistance in Chinese adults and elderly without diabetes. Arch Endocrinol Metab. Kahn HS , Cheng YJ. Longitudinal changes in BMI and in an index estimating excess lipids among white and black adults in the United States. Int J Obes Lond. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter Journal of the Endocrine Society This issue Endocrine Society Journals Endocrinology and Diabetes Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search. |

| How to Get Rid of Thyroid-Related Belly Fat | Viscerxl this happens, your body Visceral fat and thyroid health to accumulate fat around the abdomen Visceral fat and thyroid health. Fqt good news is Dietary restrictions and goals you can lose your body fat by working with, rather than against, your body. An a hormonal belly, though, your body redistributes the weight gain and instead concentrates around your middle. Decreased thermogenesis and metabolic rate in the patients with overt and subclinical hypothyroidism lead to an increase in visceral adipose tissue VAT incidence [ 6 ]. Views 1, The thyroid hormone receptor is also more activated in subcutaneous adipose tissue SAT than in VAT [ 22 ]. |

| 12 Ways to Burn Belly Fat (Visceral) | Understandably, like many women, you may find the weight room intimidating. You can learn about functional movements and the right duration and intensity to exercise. Poor blood sugar control and insulin resistance leads to belly fat gain [6]. The Standard American Diet SAD or even the healthy diet advice of eating a lot of whole grains tend to cause poor blood sugar control. Many people also are not getting their best sleep. These can lead to insulin resistance, which shows as belly fat. Inside Thyroid Strong, I recommend an Autoimmune Paleo Protocol diet and hour fasts, which can help balance your blood sugar. By lowering inflammation and being high protein, high fat, and low carb, the diet can significantly improve your insulin sensitivity [9]. Cortisol, or stress hormone, is another reason your body holds onto belly fat because it can increase your blood sugar. With chronic stress , you have more cortisol, leading to overeating and insulin resistance. There is now a well-established link between chronically high cortisol levels and weight gain [10]. Spending time in nature, practicing mindfulness, hugging a puppy, or using inexpensive meditation and sleep apps can all do wonders for lowering cortisol. Choose your own adventure here, and find your favorite stress reliever. Be sure to practice good sleep hygiene, too. Reserve the bedroom for sleep and sex only bonus: sex is a great cortisol-lowering activity! Belly fat is a problem when your hormones are imbalanced, so you want to work with someone who can help you get to the root cause. As we mentioned earlier, belly fat can be linked to insulin resistance, inflammation, high cortisol, and low estrogen. Functional medicine doctors can help you get to the root causes of these issues with laboratory testing and a thorough intake process to determine your individual health needs. These doctors usually recommend lifestyle changes, supplementation, and occasional pharmaceuticals. Exploring hormone replacement therapy for menopause. As I mentioned before, when the ovaries cease making estrogen during menopause, your body grows belly fat in an attempt to keep up with hormone production. For many menopausal and perimenopausal women, getting on an HRT protocol can result in major improvements in body composition and wellbeing [11]. It can also make it easier to reduce midsection fat [12]. That said, there are some health risks associated with HRT and it is a personal choice, so you want to do your research and speak to your doctor before making this decision. This is why I created Thyroid Strong to empower you with the right tools to help you lose weight, including in the midsection. The program will also help you regain your strength and quality of life. Affiliate disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links, which means that Thyroid Strong may earn a small percentage of your purchases if you use our links and coupon codes, while the prices will be the same or at a discount to you. This income supports our content production. Thank you so much for your support. and Guo, Y. and Tanaka, K. Arthritis Rheumatol 72 , — and Clegg, D. Lipid Res. and Djafarian, K. and Chen, T. and Karlamangla, A. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. and Debono, M. Best Pract. and Alt, A. Cureus 11 , e and Abizaid, A. and Golay, A. Maturitas 32 , — The VATs of PCF and TAT were quantized at a dedicated workstation using an MDCT Aquarius 3D Workstation. The semiautomatic segmentation technique was implemented for quantification of fat volumes. PCF was defined as the volume-based burden of total adipose tissue located within the pericardial sac Fig. The TAT tissue was defined as the total adipose tissue volume surrounding the thoracic aorta as periaortic fat , which extends Multidetector computed tomography demonstrated pericardial and thoracic periaortic fat tissue measures. A, Pericardial adipose tissue: the fat between the heart and the pericardium. B, Thoracic periaortic adipose tissue: the fat surrounding the thoracic aorta shown in axial view [ 10 ]. Orange regions indicate visceral fat tissue. The reproducibility of PCF and TAT was evaluated by performing repeated measurements of 40 randomized cases with the initial results and clinical data blinded between readers and has been published before [ 10 ]. The intraobserver and interobserver coefficients of variation for PCF were 4. The independent t test was used to test for differences in normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons involving abnormally distributed variables. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Pearson correlation analysis was used to evaluate the correlations between 5 anthropometric indices and metabolic parameters, age, and thyroid function. A P value less than. Of participants, 7. Sex is strongly correlated with obesity and CV risk factor, and we therefore compared the characteristics all participants according to sex Table 1. The SCH group comprised a greater quantity of women and older individuals than the EU group women, SCH vs EU, 52 [ Minimal differences in clinical and biochemical traits were noted between the SCH and the EU groups. Significant variations in year FRS were observed between men in the 2 respective groups SCH vs EU: Significant age discrepancies were not observed between the female participants in both groups SCH vs EU, Multivariable logistic regression models showed that the ORs for SCH increased with TAT and BRI score for women in 4 models Table 2. The independent association of TAT and BRI with SCH were stronger in female participants than their male counterparts. Odds ratio of regional-specific cardiovascular fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices with risk of subclinical hypothyroidism. Model 4: Adjusted for factors in model 3 plus SBP, FPG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and FRS. Abbreviations: ABSI, a body shape index; BMI, body mass index; BRI, body roundness index; CVAI, Chinese visceral adiposity index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FRS, Framingham risk score; OR, odds ratio; PCF, pericardial fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TAT, thoracic periaortic adipose tissue. a Model 3: Adjusted for factors in model 2 plus smoking and BMI. These association predictors were essentially unaffected by adjusting for age and lifestyle factors models 2 and 3. The TAT, BRI, and CVAI were higher in the women with SCH group SCH vs EU: 5. The incidences of TAT and BRI third tertile were also higher in women with SCH SCH vs EU, TAT third tertile, 9 [ The incidence of ABSI third tertile was higher in men with SCH SCH vs EU, 35 [ In the female participants, the incidence of region-specific CF fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices was marginally greater in individuals with SCH as opposed to the EU individuals. A comparison of the incidence of region-specific cardiovascular fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices according to thyroid functional status. Abbreviations: ABSI, a body shape index; BRI, body roundness index; CVAI, Chinese visceral adiposity index; EU, euthyroid; PCF, pericardial fat; SCH, subclinical hypothyroidism; TAT, thoracic periaortic adipose tissue. Baseline characteristics according to thyroid functional status and absolute risk of cardiovascular event in 10 years by Framingham risk score. Bold part mean statistical significant difference. Multivariable logistic regression models indicated that the ORs for SCH increased with TAT, BRI, and CVAI score for women in 3 models Table 5. The independent association was stronger in women than in men. Odds ratio of region-specific cardiovascular fat tissue and noninvasive visceral adipose indices with risk of subclinical hypothyroidism according to absolute risk of cardiovascular event in 10 years by Framingham risk score. Abbreviations: ABSI, a body shape index; BMI, body mass index; BRI, body roundness index; CVAI, Chinese visceral adiposity index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OR, odds ratio; PCF, pericardial fat; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TAT, thoracic periaortic adipose tissue. Even after adjusting for age and lifestyle factors, the association estimators remained essentially unchanged model 2. The prevalence rate of SCH in our study is 7. The main differences are the age and sex of the people involved in this study. The manifestation of hypothyroidism with CVD in VAT is well established, but the effect of SCH is unclear [ 30 ]. In the literature, different adipose compartments have different endocrine functions. It has been clearly proved that VAT will also accompany different metabolic risks and morbidities [ 31 , 32 ]. For example, VAT is a more pathogenic fat that is more likely to cause metabolism and CVD risks than subcutaneous adipose tissue [ 31 , 32 ]. A strong correlation was found between BRI and CVAI in all groups. Region-specific cardiovascular fat tissue PCF and TAT is one kind of visceral fat reservoir that is proposed to have a negative effect on blood vessels in a localized manner [ 33 , 34 ]. TAT can envelope the aorta, contributing to CV pathogenesis and potentially explaining the correlation between high TAT and SCH incidence [ 11 ]. In a previous study, the Framingham study found that even people with normal VAT had higher cardiometabolic risk if they had high TAT [ 9 ]. We did not find a relationship between PCF and SCH group in this study. Continuing epidemiological evidence shows that simple and cheap anthropometric methods can be used to predict Mets, such as BRI [ 14 ], ABSI [ 19 ], and VAI [ 35 ], which have historically been used for clinical diagnosis [ 17 , 19 , 35 ]. BRI is a predictor of body fat and VAT volume and has been postulated to be an indicator of DM and CV health status [ 17 , 36 ]. Some studies in China and Peru have found that BRI is a strong predictive index for the occurrence of Mets in men and women [ 37 , 38 ]. Based on these findings, it has been suggested that BRI could be an effective yet simple clinical screening tool for cardiometabolic risks and Mets [ 17 , 36 ]. VAI is a useful surrogate index for predicting cardiometabolic disorders in White populations [ 35 ], and the CVAI has a higher overall DM diagnostic ability than BMI, WC, and ABSI in Chinese adults [ 15 ]. Krakauer and Krakauer proposed the ABSI in , and it was found to be a better index for measuring metabolic changes and disease risk in the United States than BMI and WC [ 19 ]. Some studies have found there is a positive correlation between ABSI and disease risk and mortality hazard [ 39 , 40 ]. However, other studies have obtained opposite results [ 36 , 41 ]. Our study found that elevated TAT, BRI, and CVAI scores correlate stronger with SCH women compared to men with SCH. The rationale underlying these observations is not clear, but it may be related to sex variations in the distribution of visceral fat deposition and regional adipose tissue [ 42 ]. The mechanisms that contribute to the development of SCH from visceral adiposity may be different in men and women. In addition, age and sex are recognized risk factors for thyroid disease, and women in the third TAT, third BRI, and third CVAI tertile were older than men in the SCH group data not shown , hence SCH risk is influenced by a number of biological factors, including age, sex, and unfavorable health traits. Visceral fat deposition should be prioritized by women to reduce the occurrence of negative health outcomes. Key strengths of the study include the fact that, as far as we know, our study is the first to analyze the VAT by using noninvasive, clinically measurable surrogates BRI, ABSI, and CVAI or region-specific CV fat tissue quantified using MDCT PCF and TAT in identifying body fat distribution in SCH with different CV risk groups. Another advantage was that we analyzed for each sex. A lot of research has discussed fat distribution differences between the sexes. Our study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional data analyses cannot make causal inferences regarding the relationships between TAT, BRI, and CVAI and SCH risks. Second, after stratification, the number of participants in each group was small, which would affect the effectiveness of statistics. In the future, a larger sample size and cohort study may be needed for causality analysis. SCH participants who were at an intermediate-to-high risk of developing CAD AR 10y were significantly more likely to exhibit region-specific CV fat tissue TAT and noninvasive visceral adipose indices CVAI and BRI than EU individuals, especially in Taiwanese women. These findings suggest that mild thyroid failure also independently contributes to the development of abnormal fatty distribution. The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Jones DD , May KE , Geraci SA. Subclinical thyroid disease. Am J Med. Google Scholar. Santos OC , Silva NA , Vaisman M , et al. Evaluation of epicardial fat tissue thickness as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Endocrinol Invest. Cooper DS , Biondi B. Tseng FY , Lin WY , Lin CC , et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with increased risk for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. Wang CY , Chang TC , Chen MF. Associations between subclinical thyroid disease and metabolic syndrome. Endocr J. Dietary-induced alterations in thyroid hormone metabolism during overnutrition. J Clin Invest. Bonora BM , Fadini GP. Subclinical hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome: a common association by chance or a cardiovascular risk driver? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. Pekgor S , Duran C , Kutlu R , Solak I , Pekgor A , Eryilmaz MA. Visceral adiposity index levels in patients with hypothyroidism. J Natl Med Assoc. Peri-aortic fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and aortic calcification: the Framingham Heart Study. Pericardial and thoracic peri-aortic adipose tissues contribute to systemic inflammation and calcified coronary atherosclerosis independent of body fat composition, anthropometric measures and traditional cardiovascular risks. Eur J Radiol. Akyürek Ö , Efe D , Kaya Z. Thoracic periaortic adipose tissue is increased in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. Unubol M , Eryilmaz U , Guney E , Akgullu C , Kurt Omurlu I. Epicardial adipose tissue in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Minerva Endocrinol. Belen E , Değirmencioğlu A , Zencirci E , et al. The association between subclinical hypothyroidism and epicardial adipose tissue thickness. Korean Circ J. Iacobellis G. Epicardial and pericardial fat: close, but very different. Obesity Silver Spring. Comparisons of visceral adiposity index, body shape index, body mass index and waist circumference and their associations with diabetes mellitus in adults. Baveicy K , Mostafaei S , Darbandi M , Hamzeh B , Najafi F , Pasdar Y. Predicting metabolic syndrome by visceral adiposity index, body roundness index and a body shape index in adults: a cross-sectional study from the Iranian RaNCD Cohort Data. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. Thomas DM , Bredlau C , Bosy-Westphal A , et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Feasibility of body roundness index for identifying a clustering of cardiometabolic abnormalities compared to BMI, waist circumference and other anthropometric indices: the China Health and Nutrition Survey, to Medicine Baltimore. Krakauer NY , Krakauer JC. A new body shape index predicts mortality hazard independently of body mass index. PloS One. New anthropometric indices or old ones: which perform better in estimating cardiovascular risks in Chinese adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. Clinical surrogate markers for predicting metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Diabetes Investig. Knowles KM , Paiva LL , Sanchez SE , et al. Waist circumference, body mass index, and other measures of adiposity in predicting cardiovascular disease risk factors among Peruvian adults. Int J Hypertens. Rodondi N , den Elzen WP , Bauer DC , et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. Toth PP. Subclinical atherosclerosis: what it is, what it means and what we can do about it. Int J Clin Pract. Walsh JP , Bremner AP , Bulsara MK , et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. Razvi S , Weaver JU , Vanderpump MP , Pearce SH. The incidence of ischemic heart disease and mortality in people with subclinical hypothyroidism: reanalysis of the Whickham Survey cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III final report. A novel visceral adiposity index for prediction of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in chinese adults: a 5-year prospective study. Sci Rep. Relationship between body-roundness index and metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes. Posadas-Romero C , Jorge-Galarza E , Posadas-Sánchez R , et al. Fatty liver largely explains associations of subclinical hypothyroidism with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Abdel-Aal NM , Ahmad AT , Froelicher ES , Batieha AM , Hamza MM , Ajlouni KM. Prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with type 2 diabetes in Jordan. Saudi Med J. Després JP , Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Yudkin JS , Eringa E , Stehouwer CD. Greenstein AS , Khavandi K , Withers SB , et al. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Amato MC , Giordano C , Galia M , et al. Visceral adiposity index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care. A body shape index and body roundness index: two new body indices to identify diabetes mellitus among rural populations in northeast China. BMC Public Health. |

Wacker, der glänzende Gedanke